| Taxon ID: 23,975 Total records: 39,143 | ||||||||||||||

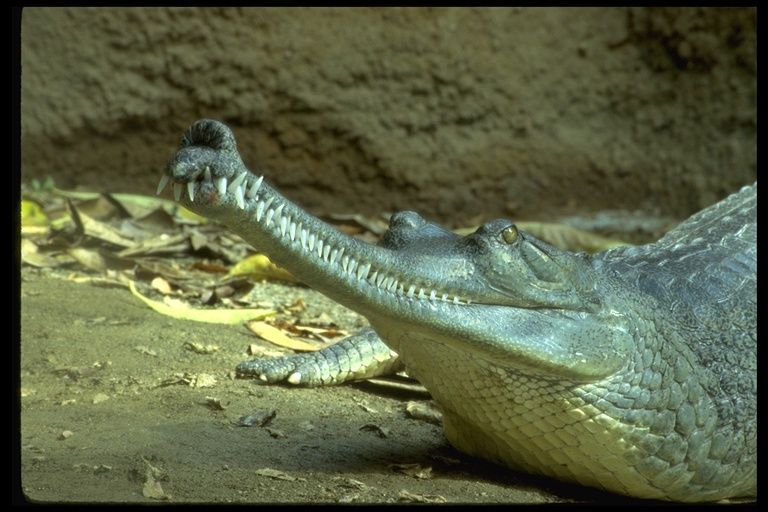

Gavialis gangeticus

Country

| Country | Myanmar |

|---|---|

| Continent Ocean | Asia |

Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia (COL) |

|---|---|

| Phylum | Chordata (COL) |

| Class | Reptilia (COL) |

| Order | Crocodilia |

| Family | Crocodylidae (COL) |

Taxonomy

| Genus | Gavialis | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SubGenus | Vernacular Name | ||

| Species | gangeticus | IUCN Threat Status-Year | Critically Endangered, 2017 |

| SubSpecies | Nat'l Threat Status-Year | Not Evaluated, 2000 | |

| Infraspecies | Reason for Change | ||

| Infraspecies Rank | CITES | ||

| Taxonomic Group | Reptiles | Native Status | Native |

| Scientific Name Author | Gmelin, 1789 | Country Distribution | Myanmar |

| Citation | Lang, J, Chowfin, S. & Ross, J.P. 2019. Gavialis gangeticus (errata version published in 2019). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T8966A149227430. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T8966A149227430.en. Downloaded on 05 March 2020. | Description | JUSTIFICATION Gharial were historically distributed throughout the major channels of the Indus, Ganges, Mahanadi, Brahmaputra-Meghna and possibly Irrawaddy drainages, to elevations of <500 m, an estimated combined linear river distance of >20,000 km, or an historic occupancy area of 80,000 km² (using Red List standard 4 km² resolution). The species is currently extirpated from the Indus, Irrawaddy and most rivers and tributaries of the Ganges and Brahmaputra-Meghna systems, but persists in fourteen sites within the Ganges drainage (6 major and 8 minor), with confirmed breeding at only five locations (Table 1 in the Supplementary Information). Surveys and counts in 2010-2017 indicate an adult global metapopulation conservatively estimated at 650 (median) with a range of 300-900. The largest and most populous location, the protected National Chambal Sanctuary in north India, spans 625 river km, with approximately 500 mature adults, comprising 77% of the global total, producing >410 nests annually, or >86% of the global total. Five other locations reporting breeding are small and highly disturbed. The remaining 8 minor locations together contain less than 10% of the world population (<50 mature adults), with no recent breeding. During the next decade, gharial will likely be extirpated from some of the minor/non-breeding sites, including three sanctuaries in India designed for their protection (Son, Ken, Satkosia Gorge), as well as the Padma-Jamuna, Brahmaputra-Meghna, and Bhagirathi-Hooghly drainages, based on the infrequent sightings in these regions. Generation time is estimated at 25 years giving a period of decline of 75 years or since 1943. Cause of declines have been principally dams and barrages disrupting river hydrology, mortality in fishing nets, and historically, unregulated hide-hunting. Current serious threats include major water control and extraction activities, mortality in fishing gear, and increased anthropogenic river-bank disruptions, especially sand mining and boulder removal. These threats are known, continuing and not reversible, therefore criterion A2 applies. The expansion of threats and major declines have intensified since the 1950s, and continue presently with increasing demand for river resources. Past population levels are inferred to be >20,000 adult gharial globally. Calculating across the range of current and past population estimates, exponential declines are 94% or greater. Even a very conservative calculation of 5,000 in 1943 and 1,000 currently gives a decline of 80%. Decline in 3 generations is confidently inferred to exceed the criterion A2bc 80% for Critically Endangered. Toxins/pollutants were strongly suspected to play a role in the death of >110 gharial in the size range of 2-4m during the winter of 2008-2009 on the lower Chambal (Whitaker et al. 2008), and possibly the loss of additional gharial in 2012 (<10-15 individuals; Nair et al. 2013). This initial major loss suggested a species-specific sensitivity to whatever caused the deaths, which were localized geographically, most occurring rapidly within 2-15 weeks. These deaths were related to articular and visceral gout, related to kidney failure, associated with low ambient temperatures. Despite the absence of a re-occurrence, the susceptibility of gharial to whatever resulted in gout in the first instance warrants the application of criterion A2e. Extent of occurrence (EOO) exceeded 80,000km² historically. Area of occupancy (AOO) is generously estimated for the six major locations with sizeable resident populations at 4,400 km², a reduction of 94%. A population estimate of 300-900 mature individuals meets criterion C1 for Endangered if we infer that the decline is continuing at a rate of at least 20% in two generations/50 years i.e. since 1967. Gharial meets criterion D1 Vulnerable (population size <1,000 mature individuals). The species does not meet criteria E. RANGE DESCRIPTION Historically, prior to 1943, Gharial were common and abundant in the main rivers and tributaries of the Indus, Gangetic and Brahmaputra drainages, and also inhabited the Mahanadi-Brahmini system in north central India. The species may have occurred in other rivers in peninsular India, such as the Godavari-Indravati rivers, as well as in the rivers and tributaries of the Irrawaddy in Myanmar, but supporting data are scant, equivocal or lacking (Singh 1991, Ranjitsinh and Singh 2002, Thorbjarnarson et al. 2006, KoKo and Platt 2012). The species is now limited to only 14 widely spaced, restricted localities in north India and lowland Nepal. Five subpopulations [Chambal River, Katerniaghat Reservoir (on Girwa River), Chitwan National Park (Nepal), Corbett National Park and Gandak River] exhibit recent reproduction/recruitment (Table 1 in the Supporting Information). Levels of nesting are commensurate with the estimated number of mature females occurring at Chambal River and at Katerniaghat Reservoir. Limited nesting, relative to the number of adult females, occurs at Chitwan, Corbett and on the Gandak River. Reproduction is not evident currently in the Babai subpopulation at Bardia NP, despite an apparently, a small number of mature females (~5-10+) inhabiting this protected stretch of river, where nesting may occur in future years. Taken together, these five locations (excluding Chambal) account for <15% of the global population, and < 14% of the known nesting abundance. Eight minor sites with no breeding evident account for less than 25 mature adults, or the remaining <5% of the gharial metapopulation. Only one locality—National Chambal Sanctuary—is an open, protected riverine habitat, with strong water flow, normal seasonal migration and natural unobstructed movements 625 km river km (A; Table 1 in the Supporting Information). The Katerniaghat locality (B; Table 1 in the Supporting Information) is very small in comparison (<20 km) and is utilised by gharial living in a reservoir behind a barrage on the Girwa River. The other four potential breeding river locations are either limited in size, unprotected or subject to disturbances from variable water flow, fishing, sand mining, cultivation: they exhibit limited or no natural recruitment. Remnant subpopulations are known at eight minor localities (G-M; Table 2 in the Supporting Information), characterized by low numbers of adults, and unfavourable, mostly unprotected habitats. Currently, in 2018, gharial are extirpated in Pakistan, Bhutan, Myanmar, and possibly Bangladesh where only few, vagrant individuals may persist. DESCRIPTION Historically, gharials were the most common river crocodylian within the species’ range, and were frequently mentioned in British India narratives describing river conditions in those areas, from the early 1800s into the 20th century (24 accounts 1834-1998 presented and discussed in Lang 2018c in press). The species survives at 14 locations (Tables 1 and 2 in the Supplementary Information), supplemented by releases of captive-reared juveniles, and an additional location where gharial appear to be successfully re-establishing themselves along a formerly occupied stretch of the Upper Ganges (Hastinapur; location O in Table 2 in the Supplementary Information). Surveys for gharial are daytime counts, conducted at seasonally favourable times of year, either by boat or from riverside observation points (=stationary counts). Boat surveys result in counts 25-40% lower than stationary counts, which provides correction factors for adjusting boat counts and compensating for the two different survey methodologies (Nair et al. 2012, Chowfin and Leslie 2014, GEP 2017). Nest counts are made by observing the number of hatched nests at the end of the hatching period (mid-June), and adding these counts to direct observations of predated nests. Sighting counts of “adult female” (3-4 m in total length; no ghara visible) are potentially biased by sub-adult males (no ghara), and nest counts although biased by uncertainty about the proportion of adult females that nest annually, are a more conservative estimate within a subpopulation. With experienced observers, the variation in estimates is not great: on the Chambal River in the NCS, 442 adult females were estimated in early 2017 and in June 2017, ~420 nests were documented (GEP 2017, Khandal et al. 2017). Major sites (six subpopulations; 1,100 km; ~600 mature adults in total): Five locations exhibit recent reproduction/recruitment and reproduction is likely at a sixth location (Babai River) in the future. Chambal subpopulation (A on Table 1 in the Supplementary Information): The single largest and most populous location, the protected National Chambal Sanctuary (NCS) in north India, spans 625 river km, and contains about 500 mature adults, based on recent, conservative survey estimates. This population comprises 77% (500/650) of the total global gharial population, with >410 nests in 2017, or ~86% of the global nest total (>410/475 nests). The Chambal subpopulation has been regularly surveyed since the 1980s, by boat counts on the stretches of river where gharial appear to live and nest year-round. Detailed nesting tallies on the lower Chambal are included in the Chambal Field Report (GEP 2017). The resident gharial in this population utilize the entire length of the 414 km of mainstream, from Pali (upstream) to Pachnada (downstream) throughout the year. In 2017, additional nests were located within the NCS protected Parvati River, an upstream tributary, joining the Chambal near Pali (Khandal et al. 2017). Nesting occurs at widely spaced sites up and down this length of protected river, changing locally every year with sandbank changes. Despite the mass die-off in the winter of 2007-2008 of ~110 gharial, 2-4 m in total length, annual counts of basking gharial and nest counts have been stable and indicate an overall moderate increase in recent years in both indices. No comparable mass mortality has occurred subsequently (Nawab et al. 2013) and die-off details are discussed in Stevenson (2015). Releases of juveniles from a conservation ranching program are still occurring and typically result in 100-200 captive-reared animals per year being released. These programmed releases are largely unstructured, unstudied and the results are not monitored. The efficacy of such releases remains unknown, and the utility of continuing the Chambal release program has been questioned. In February 2018, juvenile gharial in the MPFD release program in the NCS, which were head-started at the Deori Eco-centre, were radio tracked upon release in the lower Chambal (Lang 2018a). In comparison with other locations where gharial are still extant, the Chambal subpopulation has been relatively well-studied since the establishment of the National Chambal Sanctuary (NCS) in 1979. For decades, the Chambal River system has contained the largest, self-sustaining gharial population (Rao et al. 1995) and this region has been the focus of numerous ecological studies (Singh 1978, 1985; Whitaker and Basu 1983; Rao 1988; Hussain 1999, 2009; Katdare et al. 2011) and conservation landscape analyses (Hussain and Badola 2001). Annual surveys have been conducted (Sharma 1999, Sharma and Basu 2004, Rao et al. 2013, Sharma and Dasgupta 2013), augmented by additional surveys (Katdare et al. 2011; Nair et al. 2012a, 2012b). Interactions between Mugger Crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris) and Gharial in the NCS, over a thirty year period (1984-2014), were reported by Sharma and Singh (2014). The Gharial Ecology Project, initiated in 2008 in response to the mass die-off on the lower Chambal, has documented long-distance seasonal migrations of 100-200+ km by adults, primarily nesting females, as well as complex social behaviours of adults and young, during the pre-monsoon hatch and post-hatch period (Lang and Kumar 2013, 2016; Khandal et al. 2017; Jailabdeen 2018; Singh et al. 2018). Katerniaghat subpopulation (B on Table 1): The Katerniaghat subpopulation occupies a relatively small area, comprising about 20 km of river and reservoir shoreline, within a protected wildlife sanctuary that is part of Dudhwa National Park on the Indo-Nepal border in north central Uttar Pradesh. The Girwa River segment within it is inhabited by gharial, and is bounded downstream by the Kailashpuri Dam, a major barrage on the Ghaghara River into which the Girwa flows, and upstream by the international border with Nepal (=Geruwa River, in Nepal; eastern branch of the Karnali River). It flows from Nepal in the north into India. This location is currently estimated to contain approximately 50 mature adult gharial, 6-10 males and about 35 females. Nesting at Katerniaghat has been estimated at 24-35 nests per year, at four sites, of which the majority 22-25 are laid at one site where it is impacted by vegetation growth, and where hatchling mortality has been high in recent years.The Katerniaghat subpopulation has been studied in detail since the 1970s (Singh 1979, Srivastava 1981, Choudhary et al. 2017). This population has remained relatively constant since the last assessment (Choudhury et al. 2007), and is characterized by an annual reproductive output, in terms of number of nests, proportionate to the estimated number of mature females (30-35 females; 24-35 nests per year). Juvenile releases at this location apparently ceased after 2009, so the juveniles now in the population are presumably resulting from natural recruitment of successful in situ reproduction in this lotic reservoir habitat. At the other major locations (C-F), extant gharial sub-populations vary in the number of mature adults estimated to inhabit each area, but the level of nesting does not appear to be commensurate with the number of mature females. Rather, in contrast to Chambal and Katerniaghat, annual reproduction appears to be limited at Chitwan in Nepal, on the Gandak River in Bihar, and at Corbett on the Ramganga River in north India. Recent nesting has not yet been documented at Babai River in Bardia National Park, but did apparently occur in the 1980s (DNPWC 2018). There is potential for nesting in this protected river segment, totally within park boundaries. Chitwan subpopulation (C on Table 1): The Chitwan subpopulation is estimated to be 40-60 mature adults, with few adult males (<5 or less). At Chitwan, mature adults inhabit the Narayani and the East Rapti Rivers adjacent to the protected area, and have been recorded nesting along suitable stretches of both rivers within the last decade (Table 1 in the Supplementary Information). The number of nests found each year is relatively low, only 4 to 14 over the past decade. In most years, a majority of these nests have been removed for artificial incubation, and any resultant young were head-started by rearing in captivity for 5 to 10+ years (Archarya et al. 2017, Lang 2017b). Lower levels of nesting at Chitwan are enigmatic, but may be related to a lower reproductive frequency, e.g., biannual rather than annual nesting by females, or a recent scarcity of breeding males. Gandak subpopulation (D on Table 1): On the Gandak River (south of Chitwan in India), a separate subpopulation exists, and is fragmented into smaller groups of individuals living in a largely unprotected, riverine habitat extending over 300+ km. On the basis of recent surveys on the Gandak between Tribeni Dam on the Indo-Nepalese border and the Gandak-Ganges confluence near Patna, the resident gharial are widely dispersed, but do aggregate, primarily in the upstream 100-200 km of the river (Nair and Katdare 2014a). Although the Narayani-Gandak River is contiguous across the border, these subpopulations are treated as separate entities because there is limited exchange, especially in upstream direction, due to the water control structures on the border. In 2016, six nests were laid at a site 100 km downstream from protected habitat at the Indo-Nepal border, with successful hatching. However, in 2017, no nests were recorded, after early nesting attempts were interrupted when water was released at the upstream barrage (Choudhury et al. 2016; WTI 2017). Corbett subpopulation (E in Table 1): At Corbett National Park, gharial have been living in the Kalagarh Reservoir, occupying an approximate area 3,500-4,000ha with 32 km of shoreline habitat. Recent estimates of mature adults indicate a total of ~30 individuals, of which ~10 are males and ~20 are females (Chowfin and Leslie 2014, 2016). Nesting data at Corbett in recent years (2012-2017) are largely unavailable, but a 2013 report indicated < 13 nests (Chowfin, 2013). Earlier reports in 2008 and 2011 indicated that few nests were observed (1-2 nests; Chowfin and Leslie 2013). Hatchling mortality to one year of age is high, ~99% (Chowfin and Leslie 2016). Available evidence indicates limited nesting habitat exists, and that the reproduction rate of approximately 38% of mature females nesting annually is low. Babai subpopulation (F on Table 1): The Babai River location, entirely protected within Bardia National Park, comprises 45 km of river, bounded downstream by a major barrage and upstream by unsuitable habitat containing shallow water and rapids, which restrict gharial movements. No nesting has been detected at this locality in recent years, and there have been no young gharial observed (Lang 2016b, 2017). Nesting near Kalinara on the Babai River was noted in the 1980s (pers. comm., K.M. Shrestha, p.16, cited in DNPWC 2018). A small group of mature adults (5-10 total, including males and females) may form the nucleus of a breeding group with the potential to recover the sub-population. Head-started juveniles were released in this location in 2014 and 2015, and it is considered an excellent candidate for future releases of captive-reared juveniles (Lang 2017). Minor locations (eight subpopulations; 1,200 km; ~50 mature adults in total): Four minor locations (I, L, M, N; Table 2) have very few confirmed resident adults (<10 mature adults overall). A recent loss of large males and other adults, with habitat alteration, characterizes the Son River, Ken River, Mahanadi River, and Karnali River at Bardia NP locations. Of these, the Karnali River site (I) is possibly recoverable, if adequate protection was achieved through legislation and enforcement, and if a robust restocking program were initiated. The other locations (Son, Ken, and Mahanadi Rivers; L-N) lack adequate protection from water use, detrimental resource extraction and unregulated fishing, all of which are currently impeding recovery (Sharma et al. 2011; Nair and Katdare 2013, 2014b; Mohanty et al. 2010; Nair et al. 2017). The other four minor locations are diverse and difficult to categorize (G, H, J, K; Table 2). Two sites (Hooghly and Jamuna; H, J) are long stretches of deltaic rivers in the Ganges-Brahmaputra drainages in which small numbers of gharial have been encountered and/or documented during intermittent surveys (Ghosh and Merrill 2010; Ghosh 2013; Rashid et al. 2014; IUCN Bangladesh 2016). In these areas, shoreline and potential nesting habitats are especially transient, and residency patterns and known nesting sites have not been documented. Protection in these areas will be particularly challenging. Upstream in the Gangetic tributaries, the Ghaghara River location (G; Table 2) may contain a small number of mature adults in the middle and lower stretches, but nesting/recruitment has not been documented. Downstream movements from the Katerniaghat location upstream, probably by juveniles crossing the barrage during high water episodes, may augment gharial numbers in the Ghaghara River location (G). In recent years (2013-2017), there have been multiple releases of captive-raised juveniles in the upstream Ghaghara, in the vicinity of resident gharial sighted during recent surveys (pers. comm., S. Singh 2017) The remaining minor locations are in the Brahmaputra-Barack Rivers, grouped here as a single location (K; Table 2). Much less is known about gharial distribution and abundance in Northeast (NE) India, primarily in Assam and possibly Aranchal and Manipur (Das et al. 2013). Saikia et al. (2010) describes 11 sightings during 2004-2007, identifying four specific sites as “direct observations”, and others documented by the Assam Forest Department. One site is a natural lake, Uropod beel (=lake) where gharial have reputedly been captured and photographed (see Saikia et al. 2010). T. Ghosh (pers. comm. 2017) observed a gharial in Dibru Saikhowa National Park, and he reports local residents make additional sightings in this area. In contrast, a detailed assessment of potential gharial habitats in NE India, principally at Manas, Nameri, Orang, Kaziranga, Dibru National Parks, and D’ering Sanctuary in 2011, found no evidence of gharial in these protected areas (Das et al. 2011). Clearly, information about gharial persisting in NE India is lacking, and additional data are needed. Hastinapur subpopulation (O on Table 2): In addition to the 14 major and minor locations where gharial are extant, there is an additional location where head-started juveniles have been released from 2009 through 2017. This is a protected stretch of the upstream Ganges River mainstream, near Meerut in NW Uttar Pradesh, recently established as a wildlife sanctuary in the midst of an intensively agricultural, riverine landscape. Some juveniles released have evidently survived and become resident, mostly within the protected area. Now sub adults, they are expected to mature in the next 5-10 years. This section of the Ganges was formerly occupied by gharial, and the overall strategy for river conservation is to re-establish the resident fauna and flora, to the extent possible. This is an innovative project conducted by the WWF India Freshwater Program, in collaboration with the Uttar Pradesh Forest Department and Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change, Government of India (Yadav and Khan 2016). However, since the generation time for gharial is estimated at 25 years, the lead time before intrinsic breeding is re-established at Hastinapur is likely to be at least 5 to 15 years into the future. HABITAT AND ECOLOGY The gharial is a river dwelling crocodilian (Whitaker and Basu 1983) with adult gharial showing widespread use of river systems with seasonal migratory behaviours and social hierarchies (Lang and Kumar 2013, 2016). Gharials congregate for mating and nesting during the dry season in these highly seasonal, monsoonal rivers. Courting and mating occurs in mid–February followed by nesting and egg-laying in mid–March to early–April. Female gharial nest in seasonally exposed sandbanks along slow moving sections of medium- to large-sized rivers, and lay an average of 40 eggs. When concentrated in these areas, gharial are highly vulnerable to impacts from fishing and malicious killing. The eggs are also vulnerable because in some areas they are sought for food/medicine. Incubation takes 2-2.5 months with mostly females guarding nest sites. Hatching occurs in late May through mid-June. Adult care is well-documented. Females open the nests at the time of hatching but do not transport the young to the water. Hatchlings from multiple nests aggregate in crèches numbering from hundreds to a thousand or more. Females, and typically a single large male, guard hatchling crèches from potential predators for 1-2 months. Once monsoon waters start to rise, the guarding adults make long distance seasonal movements, and the crèches break up with hatchlings dispersing widely into aquatic shoreline habitats. Adult gharial are seasonal migrants in large, open river drainages, with movements of 50-200+ km recorded in Chambal. Upon release, non-resident, captive-reared individuals appear highly mobile, and some have moved in excess of 1,000 km. In the Chambal subpopulation, most large females nest every year (reproductive frequency >90%; Thorbjarbnarson 1996, Lang and Kumar 2016). Similar values appear to apply to other subpopulations, e.g. Katerniaghat subpopulation, but may not apply to the most northerly subpopulation, e.g. at Chitwan. The Nepalese subpopulations may show higher rates of biennial nesting. A number of gharial subpopulations now exist in lentic, rather than lotic, environments, principally in reservoirs behind dams and/or barrages, formed in flooded water courses that were formerly river channels. These include the Katerniaghat subpopulation and the Corbett subpopulation. The Chitwan subpopulation is possibly impacted by the Tribeni Dam on the Gandak (=Narayani) River, but the distances between gharial concentrations and the dams in all three locations vary. Saikia et al. (2010) sighted gharial at natural lake localities on the Brahmaputra drainage, with presence confirmed by local inhabitants. A gharial photographed by local forest department staff, was caught there and translocated into a permanent channel (Saikia 2012). Additional references on gharial habitats and ecology are noted in Groombridge (1982), Maskey (1989), Rao et al. (1995), Wildlife Institute of India (1999), Choudhury et al. (2007) and Stevenson (2015). THREATS Dams and Barrages: Major water control structures, including dams, barrages (=low, gated diversion dams) and related constructions, have been detrimental to gharial distribution and abundance on all of the river drainages in which the species occurred. These structures resulted in serious habitat fragmentation and degradation. In freshwater systems, the extinction related to dam construction is not quantified nor understood, but apparently also affects freshwater dolphins (Braulik et al. 2014, Paudel et al. 2015, Braulik and Smith 2017). In the future, many dams and barrages are planned for major rivers and tributaries in areas where Gharials reside, or are suspected to remain, such as the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra. In this area recent studies predict major detrimental effects of hydropower and storage projects on the rich and diverse fishes inhabiting the Lohit river basin, a major Brahmaputra tributary (Kansal and Arora 2012). The relatively rapid disappearance and extirpation of the formerly common and abundant gharial in the Indus system is, perhaps, the best example of the magnitude and importance of this major threat to date (Lang 2018b). Rae (1933) notes unusual, high concentrations of gharial associated with new construction of a major barrage (Lloyd Barrage) on the Indus. He observed that local fishermen related such changes in gharial behaviour directly to newly closed dam gates trapping hundreds of gharial upstream, immediately following barrage construction. Dam construction on the Ramganga River, to create the Kalagarh Reservoir at Corbett National Park, involved extensive blasting, which caused gharial deaths. The formerly large numbers of gharial that frequented the deep pools, submerged by reservoir, were reduced to a few remnant individuals (Singh 1979). On the Narayani-Gandak River, when the Tribeni Dam was constructed on the Indo-Nepalese border, gharial distribution and abundance was altered, and fewer gharial frequented the areas despite previously being abundant (Maskey 1989). Irrigation and hydro projects on the Betwa River, a major Yamuna tributary, resulted in a marked reduction and eventual extinction of resident gharial (Singh 1979). On the Brahmani River in Odisha, east central India, dam construction also involved extensive blasting, killing many gharial, and eventually leading to the species’ extinction in this drainage (Singh and Bustard 1982). On the Kosi River in eastern Nepal, which flows into India and into the Ganges, the construction of the Kosi Barrage at the international border resulted in monsoonal flooding of upstream nests, and only allowed one-way downstream movements (Maskey 2008). In Nepal, Gharial no longer survive on the Kosi, despite numerous re-introduction attempts (Shah and Paudel 2016). In India, the Kosi was channelized in the 1970s, and embankments restricted river flow. As a consequence, hunting of Gharial increased, and numbers declined dramatically (Biswas 1970; Shahi 1974). Elsewhere in Nepal, dynamiting during bridge construction at Chisapani on the Karnali River resulted in declines in resident gharial in the Bardia National Park (Maskey 1989). Water Extraction /Irrigation: Lift stations on the Chambal threaten gharial survival because during the dry season, water flow and consequently river connectivity is greatly reduced. Such activities are illegal, but persist despite restrictive legislation and regulations (Hussain et al. 2011; Nair 2017). During the last 20 years, the flow regime of the Chambal River has shown a declining trend and continued water withdrawal will negatively impact available riverine habitats important to the gharial in future years (Hussain et al 2011). Water management programs adversely impacting gharial are now evident on the Son River (location L; Table 2) (Sharma et al. 2011; Nair and Katdare 2013), and a more informed water management strategy will be needed to overcome them (Nair et al. 2016). On the Chambal, there is a major upstream project proposed that would likely divert much of the remaining water now available to the Chambal main channel, via the Parbati and Kali Sindh tributaries upon which the Chambal relies for water flow during the dry season. On the lower Chambal, its recent declaration as National Waterway No. 24, a part of the development corridor across northern India, seriously threatens this river sanctuary (Nair 2017). Vegetation intrusion at the major nesting site at Katerniaghat impacts hatchling survival (G. Vashistha per. comm. 2018). River Interlinking: The proposed Ganges-Brahmaputra inter-link canal and dam project, envisioned under the Indian National Waterways Act 2016, is intended to convert 111 reaches of 106 rivers to inland waterways for transport of cargo, coal, industrial raw materials, and for tourism, without government seeking environmental approvals for bulk of the waterways (Hindustan Times 2018). The cumulative effects of these projects will severely affect the remaining extant populations of gharial which persist in the few remaining remnants of natural riverine habitat, presently under governmental and legal sanctions as protected areas, etc. Previously, the completion of the Farakka Barrage on the lower Ganges in 1974, coupled with the construction of at least 19 other barrages and 18 high dams in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna system since 1957, resulted in major impediments to seasonal migratory movements throughout the system, and dramatic declines in the quantities and qualities of riverine habitats available to Gharial and Ganges River Dolphins (Braulik and Smith 2017). Mortality in Fishing Nets/Gear: As legal and illegal net fishing, especially with monofilament gill nets, has intensified in large rivers, gharial losses to entrapment are increasing. Data on mortality rates due to net fishing are scarce, but observations on the Chambal and Yamuna over the past decade indicate the gharials most vulnerable are young animals, primarily juveniles and sub adults, despite some large mature adults occasionally getting caught. Net related mortality is the main cause of adult losses in the Ken and Son Rivers. In 2016, on the Son River, two adult males died after being entangled in fishing nets (Nair 2017). In the Chitwan subpopulation in Nepal, one of the few resident adult breeding males was caught and drowned in a fishing net (Lang 2017). On the Chambal, fishing in the National Chambal Sanctuary is prohibited, but persists, especially in the lower reaches near the Yamuna confluence, and in the Yamuna stretches above and below the Chambal confluence. Young animals are susceptible to being caught in nets, and either drown or are killed or injured deliberately or accidentally. Older gharial appear to be “net savvy” and tend to not be captured in nets. Near the Yamuna confluence, gharial of all sizes with damaged snouts are more often encountered than elsewhere in the NCS. Sand Mining and Boulder Collection: Sand mining removes critical riverside substrate for nesting. Increasing and widespread development has resulted in high demand for sand for construction purposes. Sand removal operates on an industrial scale at some localities on the Chambal River, and also on the Ken and Son Rivers, as well as at unprotected minor locations where gharial still survive. In Nepal, boulder removal in addition to sand mining continue on unprotected stretches of river adjacent to and within both Chitwan and Bardia National Parks. Sand mining continues at a number of Gharial localities, and has widespread and detrimental effects on wildlife directly, as well as on the integrity and lateral connectivity of these important riverine habitats (Vagholikar and Moghe 2003; Taigor and Rao 2008, 2010a, 2010b; Nair and Katdare 2013, 2014b; Nair 2017; Lang and Kumar 2013, 2016; Rao et al. 2016; Nair 2017). Introduced Species: Exotic fish species are now established and common in the Yamuna-Chambal system. Feral, exotic Tilapia species are now the most abundant fish in sample catches at multiple stations on the lower Yamuna (Ganie et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2014). Although Tilapia were suggested to be a major contributor to the mass die off of gharial in 2007-08, there is scant evidence to support this suggestion (Stevenson 2015), despite the fact that this species is known to contain high levels of industrial effluents and pollutants in Yamuna waters (Laxmi et al. 2015). A preliminary study in the NCS identified the dominant species of Tilapia to be T. mossambicus and fish from the upper Chambal were in better body condition than those collected in the lower Yamuna (Rainwater et al. 2009). Downstream, the dominant tilapia species is T. niloticus (Dwivedi et al. 2016) although both species are found. Monsoon observations by Gharial Ecology Project researchers indicate that there are regular, seasonal concentrations of Gharial (> 50+), primarily adults and large sub adults, assembled at the confluence of the Yamuna-Chambal rivers for feeding when currents and water levels are conducive. The dominant fish being caught and consumed by Gharials participating in these feeding aggregations is tilapia, and typically many fish are consumed by individual animals, on any given day when conditions are favourable (Lang and Kumar 2013, 2016, and unpublished observations). Elsewhere, the production of a strong male-bias in populations of the American Crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) has been attributed to a novel environmental androgen added to fish feed (methyl testosterone) for rapid growth in Tilapia aquaculture operations adjacent to the natural riverine habitats of the affected crocodiles (Murray et al. 2017). The possible effects of Tilapia consumption, a relatively new food source for Chambal Gharial, have not yet been studied, but may be noteworthy, with reference to the recent mass die-off, as well as to environmental influences on sex determination (Lang and Andrews 1994, Andrews and Whitaker 2004), growth and overall health. USE AND TRADE Eggs are known to be harvested as a food source and for medicinal purposes by river-dwelling local societies on the Girwa and the Rapti – Narayani Rivers (Choudhury et al. 2007). Hunting of the species is no longer considered a significant threat (Choudhury et al. 2007). Gharial do not contribute to the local economies through consumptive uses but are featured in eco-tourism, which is primarily bird-based, at multiple localities in all three states along the National Chambal Sanctuary. CONSERVATION ACTIONS For nearly half a century, serious concerns have been expressed about the status and continued survival of Gharial populations globally (Biswas 1970; Bustard 1975, 1999; Whitaker 1975, 1987; Maskey 1999, 2008; Sharma and Basu 2004; Choudhury et al. 2007). In a recent commentary and review, Stevenson (2015) outlined a brief history of these conservation initiatives for gharial, and evaluates successes and failures. These efforts have included ex-situ activities focused on enhancing existing populations and re-establishing populations in places where the species has been extirpated. Ex situ activities include production of juveniles through conservation ranching and captive breeding, with releases and introductions into wild habitats. In situ activities, focused on enhancing and strengthening existing populations, include habitat protection, direct species protection measures, and local community programs aimed at species’ protection and continued survival. Head-starting: Conservation ranching of wild eggs, with rear and release programs, were at the centre of initial conservation actions in the 1970s and 1980s, in both India (Bustard 1999) and Nepal (Maskey 1999). To date, in excess of 6,000 Gharial have been reared and released in both countries (India: ~5,000; Stevenson 2015; Nepal: ~1,000; Khadka et al. 2013, Lang 2016b; Acharya et al. 2017). However, the success of these programs is open to question, and remains largely untested. The initial restocking of suitable habitats such as the Chambal and Katerniaghat in India contributed to curbing the rapid rate of population decline prior to 1970s, helped stabilize existing numbers, and led to eventual population increases in selected localities. In fact many of breeding adults now living in the National Chambal Sanctuary may be animals released as juveniles 10 to 30 years ago. But a lack of any robust marking protocols or systematic follow-up on the fate of such releases, preclude objective evaluation of their effectiveness. Elsewhere, repeated releases of head-started juveniles have not resulted in appreciable population increases, and the fate of released individuals are either not known (Stevenson 2015) or known to have not succeeded in boosting the wild population (Shah and Paudel 2016, Acharya et al. 2017, Lang 2017). In general, relative to other species such as alligators, gharial eggs have proved difficult to transport and incubate successfully under artificial conditions. Likewise, developing suitable techniques for rearing gharial hatchlings (which prefer to feed on live fish) that thrive and grow in captivity has proved challenging. The head starting of gharials has proven to be more difficult than anticipated, expensive and has not become the panacea for gharial conservation anticipated, particularly when resources and manpower are in short supply. Captive breeding: In India, successful captive breeding programs were established for gharial in the 1980s and 1990s, notably at Nandan Kanan in Odisha, at the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust in Tamil Nadu and at the Kukrail Breeding Center in Uttar Pradesh (Bustard 1984, 1999; Whitaker 1987). These facilities, in turn, produced young Gharial for the various release programs, as well as for exchanges with Asian and international zoos worldwide. In Nepal, the major sources of gharial for the head-start programs have been ex situ incubation of eggs from wild nests, but this strategy has been augmented in recent years by captive breeding (Khadka et al. 2013). Outside of south Asia, success in the captive breeding of gharial in zoos has lagged behind successful programs for most other crocodilian species but recently there have been some notable successes in Europe and in the USA (e.g., Crocodile Zoo Protivin in Czech Republic; Saint Augustine Alligator Farm, Florida). Release strategies: Within a decade after the start of Project Crocodile in India, more than a thousand raised juvenile gharial, 2 to 5 years of age, were released back into protected habitats (Whitaker 1987). In addition to releases in the National Chambal Sanctuary, gharial were released in the Girwa, Sharda, Ramganga, main Ganges, Betwa, Ghaghara, and Suheli Rivers (Bustard 1999). In the intervening years, prior to the species’ listing to Critically Endangered in 2007, releases have continued apace, but as Bustard (1999) noted earlier, “no systematic monitoring is being carried out”. Since 2007, releases have continued, but are poorly documented by individual state Forest Departments within India. These have occurred at localities inhabited by Gharial at Chambal, Girwa (=Katerniaghat), Ghaghara, Gandak, and Ken Rivers. In addition, head-started Gharial have been released in previously occupied habitats, including the Upper Ganges in protected sanctuaries, at Hastinapur in Uttar Pradesh, and at Haricke, in a reservoir on the Beas River, a tributary of the Indus in the Punjab, India. These latter two releases are re-introductions of juvenile Gharial back into riverine habitats from which gharial had been extirpated previously. Here the objective is to re-establish Gharial where they used to occur historically, but were eliminated in recent times. Similar efforts were made in the Koshi River, Nepal on repeated occasions in the 1980s and 1990s, but these earlier attempts to re-establish gharial failed (Shah and Paudel 2016). Recent releases in Nepal (2007 to 2016) at Bardia and at Chitwan have not resulted in appreciable population increases (Acharya et al. 2017). |

| Source |

Record Level

Growth Parameters

| Temperature | 0 | Observed Weight | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Previous Catalog Number | ||

| Life Stage | Relationship Type | ||

| Preparation Type | Related Catalog Item | ||

| Individual Count | 0 | GML Features | |

| Observerd Individual Count | 0 | Notes |

Collecting Event

Images

|

Additional Info

Synonyms To Manage Synonyms for Gavialis gangeticus, click this link: Synonyms. |

Crocodilus arctirostris Daudin, 1802 ¦ Crocodilus gavial Bonnaterre, 1789 ¦ Crocodilus longirostris Schneider, 1801 ¦ Crocodilus tenuirostris Cuvier, 1807 ¦ Lacerta gangetica Gmelin In Linnaeus, 1789 ¦ Rkamphostoma tenuirostre Wagler, 1830 ¦ |

Common Names To Manage Common Names for Gavialis gangeticus, click this link: Common Names. |

Gharial () |

Localities To Manage Localities for Gavialis gangeticus, click this link: Localities. |

Species Record Details Encoded By:

Carlos Aurelio Callangan

|

Species Record Updated By:

Carlos Aurelio Callangan

|